Editor’s note: April 30, 2025, marks the 50th anniversary of the fall of Saigon and the end of the Vietnam War. In commemoration, Military Times is highlighting stories about the Vietnam War.

By March 1975, the situation in Vietnam, and South Vietnam specifically, was dire. Gen. Nguyen Van Thieu, the last in a long line of military dictators propped up by the United States was, according to historian Edward Rasen, “making decisions based on his daily astrological chart, while Graham Martin, U.S. ambassador to Vietnam, had terminated daily CIA briefings, threatened to ‘cut the balls off’ CIA Saigon station chief Tom Polgar, and was becoming increasingly detached from the reality on the ground.”

South Vietnam was unraveling.

As of March 14, Thieu had conceived a strategy “called ‘light at the top, heavy at the bottom,’ pulling forces out of northern South Vietnam and concentrating them around the palace … because he was concerned his military commanders might move against him,” according to Frank Snepp, the CIA’s chief analyst in Vietnam in 1975.

“He went to Cam Ranh Bay and his message was, let’s pull the Airborne back, let’s shift them around. But he didn’t follow through. He didn’t tell his commanders about his timetable, so when the North Vietnamese moved out of the Central Highlands and concentrated in Military Region 1, the South Vietnamese army was in a confused state. That was one of the reasons they collapsed so rapidly.”

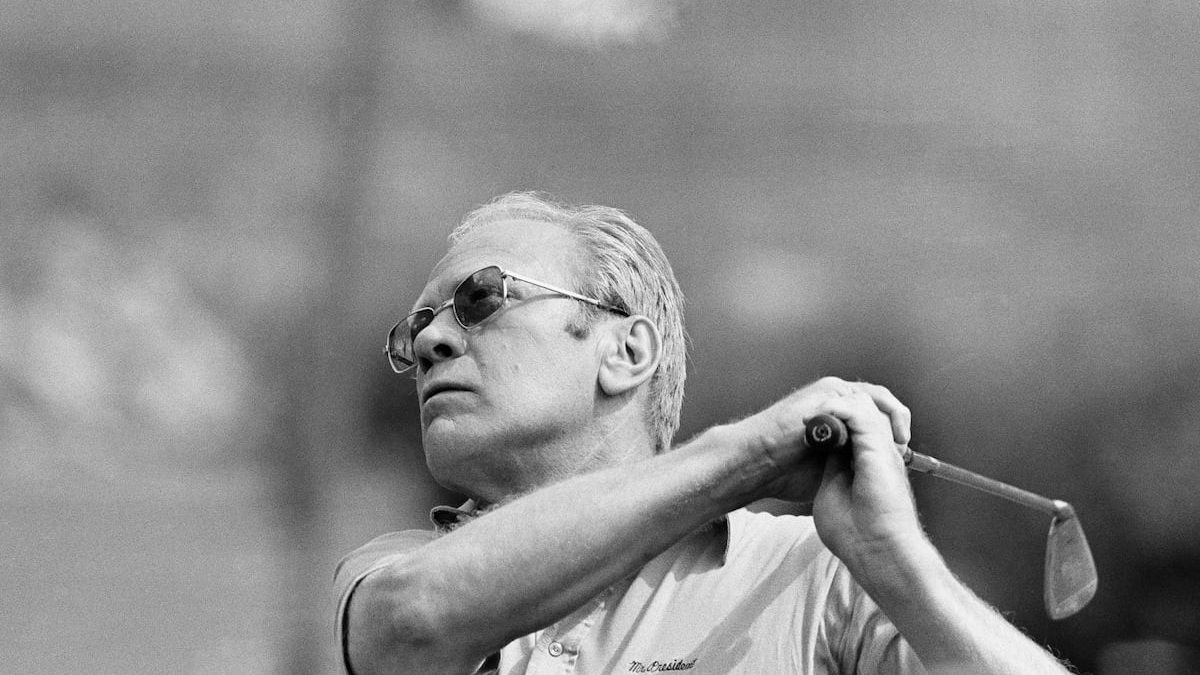

And where was America’s president? Golfing.

Amid the rapidly accumulating military losses in South Vietnam, President Gerald Ford was in Palm Springs, California, on an eight-day Easter holiday. Staying with his golfing buddy, Fred C. Wilson, founder of the Trans World Insurance Company, Ford played several rounds of golf, including one with Bob Hope, Leon Parma and William G. Salatich, president of the Gillette Company.

“He’s just a real good guy,” Wilson told a reporter on March 30, 1975. “I want to help him have a real good time and help him relax as much as possible.”

Having less of a “good time” was Ford’s White House press secretary, Ron Nessen, who had to go into PR crisis management to attempt to show both the American people and the South Vietnamese that the president’s golf games did not, in fact, make him indifferent to the military crisis and the plight of hundreds of thousands of refugees in Vietnam.

On March 31, 1975, Ford dodged reporters by breaking out into an all-out sprint when asked by a reporter what he was doing about the “military losses of the South Vietnam Government,” according to a report by the New York Times.

“‘We are trying to get to the plane,’ he replied as he and his entourage jogged toward the Presidential jet.”

According to the New York Times, Nessen stated Ford “had been receiving complete information from Washington on the war, was concerned about it and ‘feels a great deal of compassion.’”

Yet, as the New York Times stated, “The Vietnam situation, however, has not disrupted the President’s vacation schedule. Mr. Nessen has repeatedly told reporters that there is nothing more Mr. Ford can do or say.”

Receiving a report on April 5 from Gen. Fred Weyand, Army chief of staff and former commander of the Military Assistance Command Vietnam (MACV), who had just departed Saigon after assessing the situation, the president was told amid the luxe background of Palm Springs that “the current military situation is critical and the probability of the survival of South Vietnam as a truncated nation is marginal at best.”

Just 19 days later, U.S. Secretary of State Henry Kissenger, in an urgent cable to Graham Martin, U.S. ambassador to South Vietnam, wrote that his “ass isn’t covered. I can assure you I will be hanging several yards higher than you when this is all over.”

Saigon would fall less than two weeks later.

Presidents who golf

Ford wasn’t the first president to draw the ire of the American public for his extracurricular activities, however, and he wouldn’t be the last.

Since William Taft — who, in 1909, became the first president to pick up the sport — numerous chiefs of state have taken to the green as a form of exercise, stress relief and even as an act of diplomacy.

President Woodrow Wilson logged the most time on the green, playing more than 1,000 games of golf during his eight-year presidency, even during the height of American military action during the Great War. President Dwight D. Eisenhower was not far behind, famously playing more than 800 rounds during his time in office.

President George W. Bush caught flak for his 2002 comments in which he addressed suicide bombers in Israel before adding, “Now, watch this drive!”

President Donald Trump has been equally criticized for his love of the game against the backdrop of a global pandemic and now, in his second term, amid his sweeping tariff policies and skipping the dignified transfer of four U.S. soldiers killed while training in Lithuania.

Bill Clinton, however, remains an ardent supporter of the game, telling Golf Digest in 2012, that the game was critical to help a president unwind.

“Presidents need to rest their minds, not just their bodies,” Clinton said. “They need the exercise, the fresh air. And they need to do something that, literally, takes them away from what they’re doing.”

Saigon falls

Less than a month after Ford’s excursion under the warm California sun, the eerie sounds of Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas” could be heard around Saigon, but it wasn’t to mark the approaching holiday season, it was the American code signaling the start of Operation Frequent Wind — the evacuation of Saigon.

Beginning on April 29, 1975, Armed Forces Radio jarringly blasted the Christmas song throughout the bombarded city as increasingly panicked American and South Vietnamese clamored to reach the safety of the U.S. Embassy and its evacuating helicopters.

For two days helicopters landed on the embassy’s roof every 10 minutes, moving more than 7,000 people out of Saigon.

This time, however, Ford was firmly at his desk in Washington. No greens to be seen.

Claire Barrett is the Strategic Operations Editor for Sightline Media and a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.

Read the full article here