This soldier became the first Hispanic American MOH recipient of WWII

The Japanese occupations in June 1942 on the Aleutian islands of Attu and Kiska, originally planned as a feint to divide the U.S. Navy at the onset of the Battle of Midway, would fail to prevent the empire’s naval disaster.

It did, however, open up a new front, threatening Allied sea lanes in the northern Pacific and placing enemy boots on American soil for the first time since 1815.

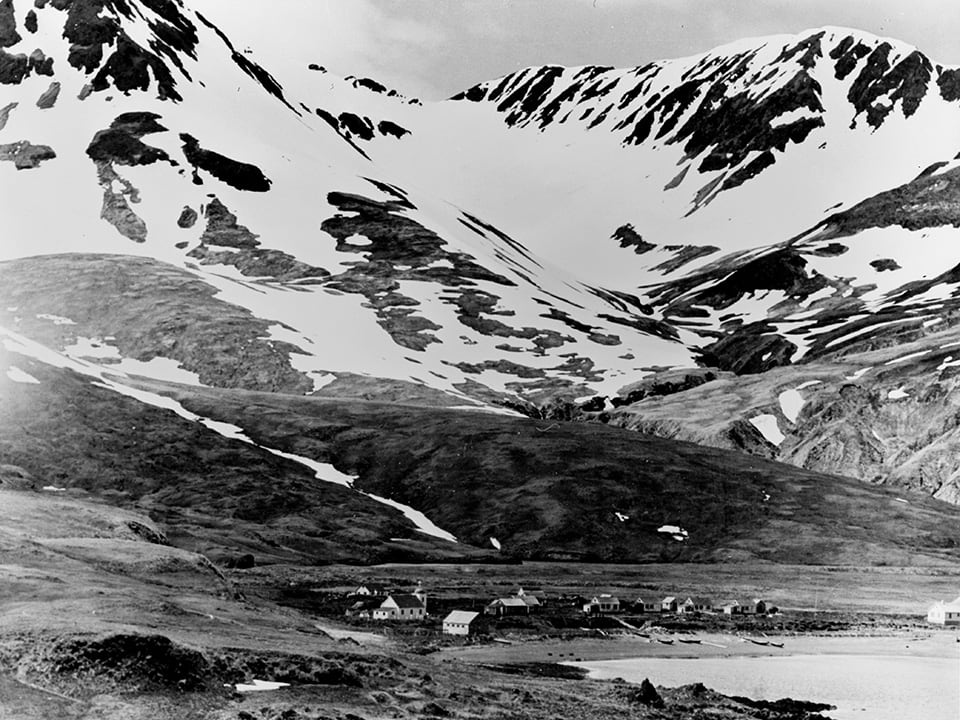

After months of air and sea engagements that gradually isolated the Japanese-occupied territories, 15,000 U.S. Army soldiers of Maj. Gen. Albert E. Brown’s 7th Infantry Division, aided by Royal Canadian Air Force warplanes, launched Operation Landcrab, coming ashore on Attu on May 11, 1943.

With a garrison of no more than 2,900 at his disposal, the Japanese commander, Colonel Yasuyo Yamasaki, abandoned any thoughts of defending the beachheads, instead withdrawing his men into the mountains, where they would inflict the maximum possible casualties before being inevitably overwhelmed.

RELATED

It was a strategy similar to those used later on Peleliu, Tarawa, Iwo Jima and Okinawa. In contrast to those successors, however, Attu would see the only time during World War II that American and Japanese troops fought in the ice and snow.

It would also see an outstanding battlefield performance from an unlikely protagonist.

Joseph Pantellion Martinez was born in Taos, New Mexico, on July 27, 1920, the youngest son of Jose Manuel Martinez and Maria Eduvigan Romo. In 1927 the family moved to Ault, Colorado.

In August 1942 Martinez, then 22 years old, was drafted and sent to basic training at Camp Roberts, California. He was then assigned to Company K, 32nd Regiment, 7th Infantry Division, most of whose troops had underwent similar training and were utterly unprepared for the Arctic conditions under which they would make their fighting debut.

From the landings at Attu’s Holtz Bay on June 11, the 7th Division troops were caught up in a slow slog from the terrain and weather, as well as fighting that ranged from mortars and artillery to hand-to-hand with bayonets. For his part, Pvt. Martinez raised K Company’s firepower with a Browning automatic rifle, or BAR.

By late May, the Americans had reached a knifelike mountain ridge flanking a snow-covered defile, from which the Japanese defenses, towering 150 feet above them, managed to hold for several days.

As Martinez’ citation described the situation, “Repeated efforts to drive the enemy from a key defensive position high in the snow, covered by precipitous mountains between the east arm of Holtz Bay and Chichigof Harbor had failed.

“On 26 May 1943, troop dispositions were readjusted and a trial coordinated attack on this position by a reinforced battalion was launched. Initially successful, the attack hesitated.”

At that point Martinez literally rose to the occasion.

Springing forward, he advanced on his own, taking out one enemy defensive position after another using his BAR and grenades, pausing only to urge every soldier he met to revive the assault.

Success bred success with each enemy position Martinez eliminated. His comrades, inspired by his example, joined in the uphill charge.

Destroying several more enemy sites, Martinez ultimately reached a 15-foot rise called the Fishhook. From the elevated position he began firing into a last enemy trench, when one of its occupants shot him in the head.

Martinez’s fellows were keen to rush him back to a medical facility, but the continuing struggle beyond the ridge rendered that impossible.

The next morning, K Company discovered that the Japanese, judging their position untenable, had all withdrawn, but it was too late for Joe Martinez, who died of his head wound.

“The pass, however, was taken,” his citation noted, “and its capture was an important preliminary to the end of organized resistance on the island.”

With the Americans’ principal obstacle overcome, on May 29 Colonel Yamasaki, judging his forces no longer capable of stalling them, ordered a final act of desperation that also became a common grisly coda to any Pacific island facing imminent defeat: a final suicidal assault en masse — in this case the only such banzai charge on American soil.

Personally leading his men with sword drawn, Yamasaki led a contingent into the American rear at Engineer Hill before being cut down. In the aftermath, the Americans buried 2,351 Japanese and took 29 prisoners — none of whom were officers — while losing 547 men killed, 1,149 wounded and 1,814 suffering from frostbite or related casualties.

As Allied forces massed for a larger landing at Kiska Island, on July 28 a Japanese naval force slipped through the fog, deftly evading the Allied fleet, to evacuate all its personnel.

With that, the Japanese occupation of the Aleutians ended.

Back in Ault, Colorado, on Nov. 11, 1943, Martinez’s family received his posthumous Medal of Honor from Brig. Gen. Frank L. Culin Jr.

Martinez was the first Latino American, as well as the first New Mexican, the first Coloradan and the first private, to receive the Medal of Honor during World War II.

A Boulder Victory-class cargo ship named for him, the USNS Private Joe P. Martinez, served during the Korean War. Among other dedications, a bronze statue of Martinez, carrying his BAR, can be seen in Denver.

Read the full article here