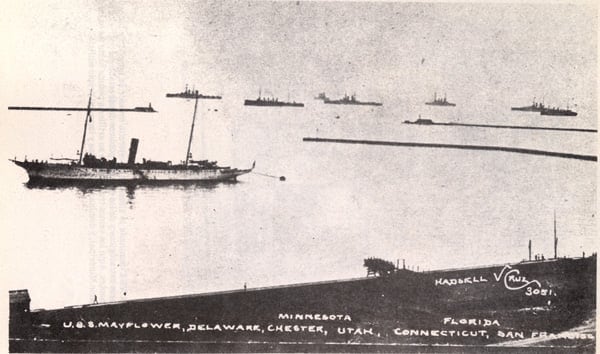

British, French, German, Spanish and Dutch navies ringed the harbor surrounding the Mexican port of Veracruz in observation of America’s soon-to-be, short-lived occupation of the city-state.

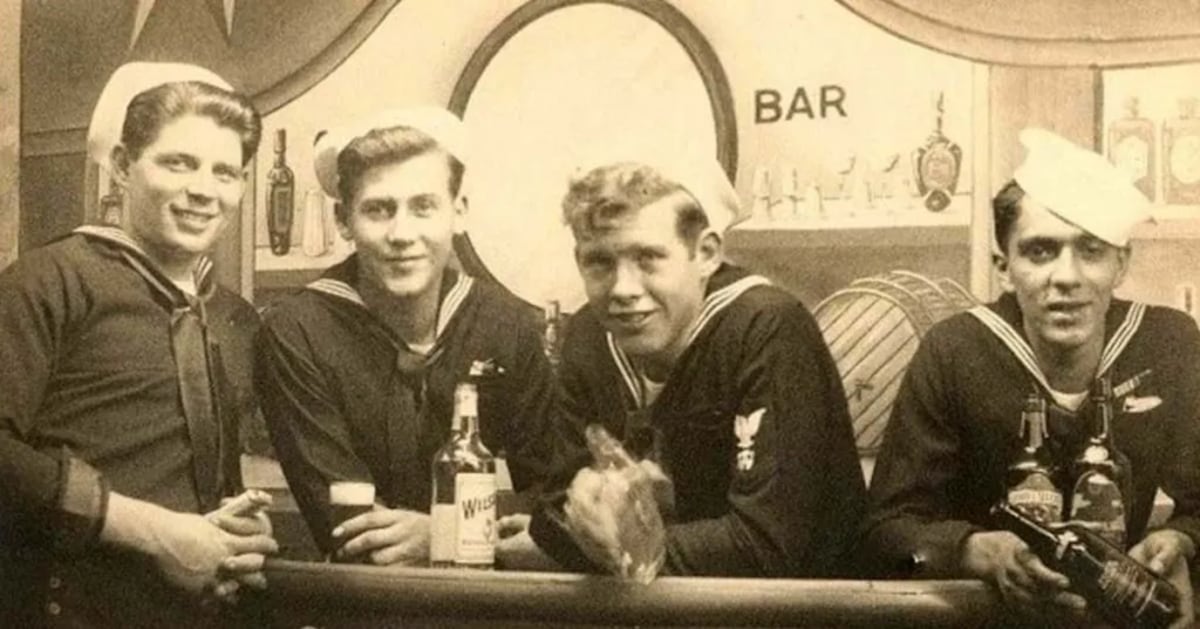

The gathering marked one of the last peaceful interactions between the navies for half a decade. The date was June 30, 1914, and the sailors were getting blitzed, courtesy of Uncle Sam and his teetotaler secretary of the Navy, Josephus Daniels.

On April 16, 1914, Daniels issued the infamous Order No. 99, mandating all U.S. Navy ships become dry by July 1, 1914.

“The use or introduction for drinking purposes of alcoholic liquors on board any naval vessel, or within any navy yard or station, is strictly prohibited, and commanding officers will be held directly responsible for the enforcement of this order,” reads the century-old order.

The order was met with derision and merciless mockery in the media. Dubbed Daniels “Sir Josephus, Admiral of the USS Grapejuice Pinafore” by the press, editorial cartoons charged him with making the Navy “soft” and showcased Navy warships bedecked with flowers, rocking chairs and potted plants, according to the U.S. Naval Institute.

Since its inception, the U.S. Navy had been providing sailors with a daily ration of rum. In 1794, sailors were to receive “one half-pint of distilled spirits” each day. In 1806, sailors were encouraged to swap out the more expensive rum for a ration of whiskey.

That ration was reduced in 1842 to “one gill” (four ounces) and eliminated altogether during the American Civil War — albeit the Confederate Navy continued to imbibe.

The tradition picked back up after the war, with sailors — at the discretion of their commander — allowed to keep their own stock of beer and undistilled spirits.

The 1899 Philippine-American War once again limited the flow of bevvies, banning enlisted men from purchasing alcohol “either on board ship, or within the limits of navy yards, naval stations, or marine barracks, except in the medical department.”

“By the time General Order No. 99 was announced,” writes the U.S. Naval Institute, “the only alcohol left in U.S. Navy ships was reserved for the wardroom and the captain’s wine messes. As the deadline approached, many of the ships of the Atlantic Fleet were in Mexican ports, part of the occupation of Veracruz.”

Enter: One raucous party.

As the shot clock waned on the soon-to-be illicit cargo, commanders rushed to offload as much alcohol as they possibly could before the “bone-dry” date. However, many were unable to sell off their sizable supply of booze and decided to host one final farewell.

With much of the U.S. Navy in and around Veracruz, the Mexican port soon saw its cups, quite literally, runneth over.

Themed parties, such as Wild West saloons, broke out, while other vessels held funerals “where mourners could watch John Barlycorn’s burial at sea,” writes the Naval Institute.

A few ships decided to absolutely obliterate their collective livers by pouring all the alcohol they had on board into one large bowl, à la bathtub jungle juice.

Soon, the British, French, German, Spanish and Dutch, who were likewise harbored outside of Veracruz, got in on the act, launching roving drinking parties from ship to ship to help the Americans rid themselves of the soon-to-be contraband.

While other U.S. ships around the globe held similar boozey farewells, none matched the scale and international participation of that in Veracruz.

The good times would not last, however. In less than a month, the participants faced the sobering reality of a world at war.

Less than a year after sharing spirits in Mexico, writes USNI, the German cruiser Dresden was subsequently hunted down and scuttled by the Royal Navy.

Claire Barrett is the Strategic Operations Editor for Sightline Media and a World War II researcher with an unparalleled affinity for Sir Winston Churchill and Michigan football.

Read the full article here