The men and women aboard the Navy destroyer Carney could be forgiven for thinking they were headed toward a quiet cruise on Oct. 7, 2023, as the warship steamed east across the Atlantic Ocean to begin its latest deployment.

But that day heralded the start of a great upending for the U.S. Navy, after Hamas militants streamed into Israel and murdered more than 1,200 people, sparking a war that continues to threaten to engulf the Middle East to this day.

RELATED

The moment that would change the Navy forever actually took place aboard the Carney 12 days later, on Oct. 19, when it became the first American warship to take out a barrage of Iran-backed Houthi rebel missiles and drones fired from Yemen.

Such intercepts have since become a harrowing, near-daily occurrence for destroyers in those waters, and the year that followed Oct. 19, 2023, has irrevocably changed the Navy for the foreseeable future, Navy leaders and outside analysts say.

On this day one year ago, starting around 4 p.m. local time, Carney took out a Houthi attack the Pentagon later said was headed for Israel, downing 15 drones and four land-attack cruise missiles over 10 hours.

While their pre-deployment training prepared them for anything, the Carney was not expecting to find itself taking on the Houthis in a near-daily battle to keep the claustrophobic Red Sea lanes open for commerce, Cmdr. Jeremy Robertson, the ship’s commanding officer for that cruise, told Navy Times this week.

“None of us really could have known what we were going to get into once Oct. 7 happened,” he said.

Since those fateful 10 hours a year ago, the Red Sea has become the arena for the longest sustained “direct and deliberate attacks at sea” that the fleet has faced since World War II, Fleet Forces Command head Adm. Daryl Caudle said in a statement to Navy Times.

“While I could not have predicted the complexity and interrelationships of all that has transpired since [Oct. 19, 2023], I am not surprised,” said Caudle, who commands the Navy East Coast-based fleet.

RELATED

“The world is a very tense place right now given the vast range of power-seeking agendas between peer competitors and opportunistic regional proxies. Any small spark can have serious consequences, which is why we take every situation so seriously.”

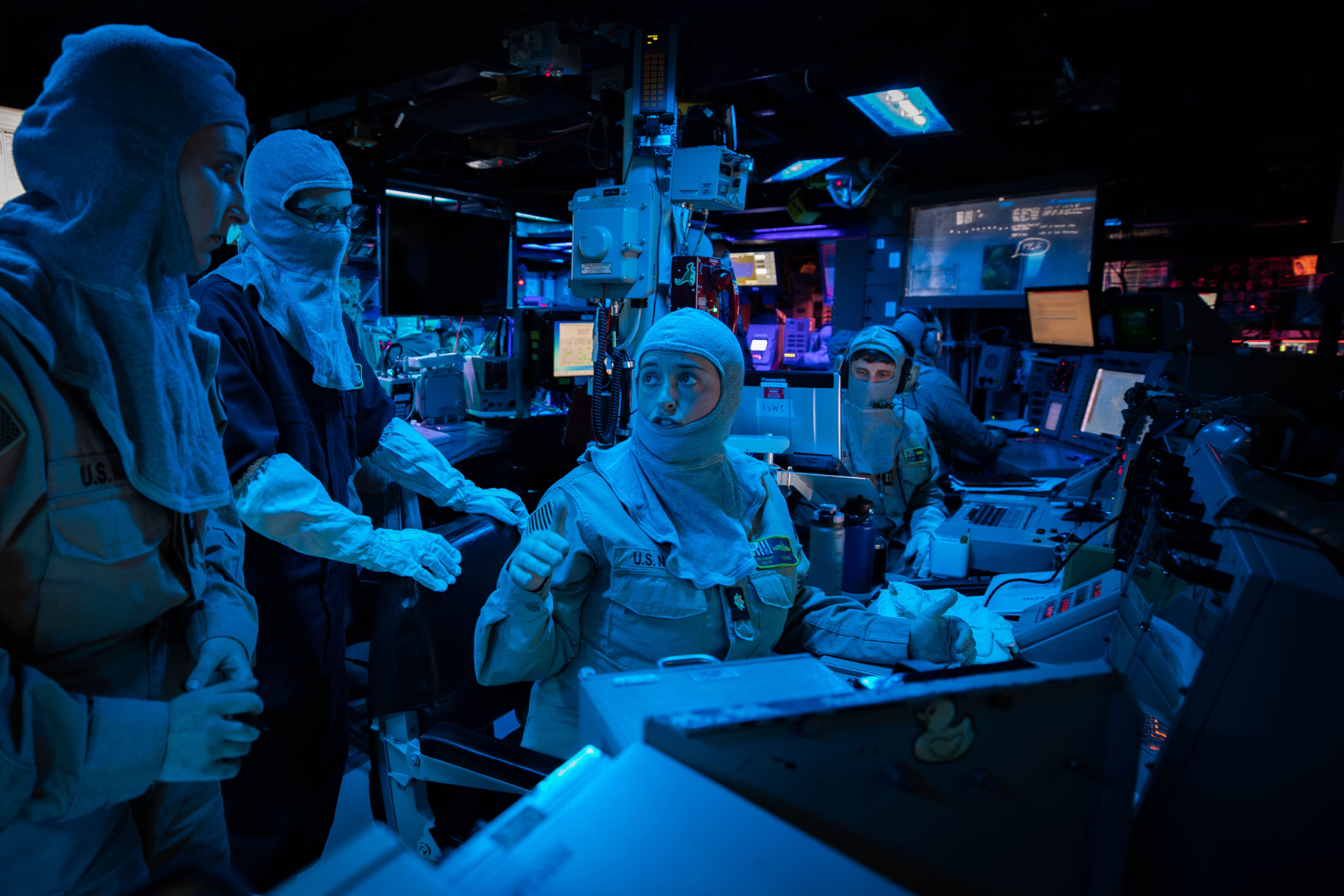

Since Carney’s first victory, the surface fleet has subsequently honed its tactics and tuned its radars for such a fight, instances when a ship’s Combat Information Center sometimes has mere seconds to ascertain and take out a Houthi attack.

Combat lessons are being routed back to schoolhouses and training centers, giving the Navy real-time knowledge on its combat systems and how to best use them.

Skippers also report that their crews have been galvanized by such experiences, finding meaning to their seemingly endless training in the life-and-death minutes they endure in the Red Sea and Gulf of Aden.

“This really gave our sailors the why,” Robertson said. “Why do we train so hard, why do we do all the reps and sets.”

“The stage was not too big, the lights were not too bright. They were able to draw a connection.”

These successes at sea “validate our readiness to respond, our Sailors’ warfighting spirit and the technological superiority of our exquisite combat systems,” Caudle said.

But despite the tactical successes and demonstrated proficiencies, some question how fast the Navy is burning through munitions, sometimes to take out cheap Houthi drones, and whether a drawdown of missiles could one day impact a long-feared war with China in the West Pacific.

The Houthi menace in the Middle East has also caused the Navy’s aircraft carriers to be run hard, and some have been scrambled to the region when others weren’t ready to go, further raising readiness alarms in some corners.

And while tactical battles have been won, strategic wars have not, according to James Holmes, a retired Navy gunnery officer and professor of maritime strategy at the Naval War College.

“The tacticians have done their work magnificently … and the combination of sensors, fire control and weaponry has performed as advertised against an array of threats similar to what [Iran, Russia and China] field,” Holmes told Navy Times. “Bringing down anti-ship ballistic and cruise missiles is no easy feat, but they have done it.”

RELATED

And while such successes will reverberate on other maritime battlefields, the Navy to date has been unable to stop the Houthis from attacking merchant vessels traveling through the vital economic waterway that is the Red Sea, he said.

“The failure part is that the mission has fallen short of its strategic goal, namely allowing merchant shipping through the Gulf of Aden, Bab el-Mandeb Strait, and Red Sea to resume unmolested,” Holmes said. “We can flip strategic failure to success when shipping firms — and the all-important maritime insurance companies — feel comfortable enough to start using that route again.”

A year in, the Navy is getting more judicious about how it fights Houthi attacks, according to Bryan Clark, a retired submarine officer and analyst at the Hudson Institute think tank.

Navy ships threw the “kitchen sink” at incoming drones and missiles after the Carney’s first intercept a year ago, but the fleet is becoming more adept at using electronic warfare, guns and less-expensive interceptors to counter such Houthi attacks, Clark said.

Questions of sustainability of effort are now arising, he said, noting that the Navy has in some instances used carrier-based fighter jets to shoot down Houthi drones and missiles, an expensive and inefficient approach.

“The challenge going forward will be how to sustain this level of presence in the region,” Clark said. “The Pentagon may need to consider putting missile defense systems on barges or ashore so [destroyers] can deploy elsewhere or return home for maintenance.”

Robertson left the Carney after it returned to Mayport, Florida, in May, and is now the Navy’s Surface Warfare Advanced Tactical Training, or SWATT, director, passing on his hard-earned knowledge.

“It’s certainly surreal,” he said of his time commanding Carney. “I love every one of the sailors and officers and chiefs I worked with. Just a great crew. They’ll remember this for the rest of their lives.”

As the one-year anniversary of Oct. 19 comes and goes with no end in sight for the Navy’s Red Sea fight against the Houthis, Caudle noted that it’s difficult to forecast how the conflict will end.

“While I won’t speculate on how our involvement with the Houthis will culminate, I can tell you that I’m laser-focused on readiness, sustainment and lethality,” he said. “We’re ready for this fight, not matter how long it lasts.”

Geoff is the managing editor of Military Times, but he still loves writing stories. He covered Iraq and Afghanistan extensively and was a reporter at the Chicago Tribune. He welcomes any and all kinds of tips at [email protected].

Read the full article here