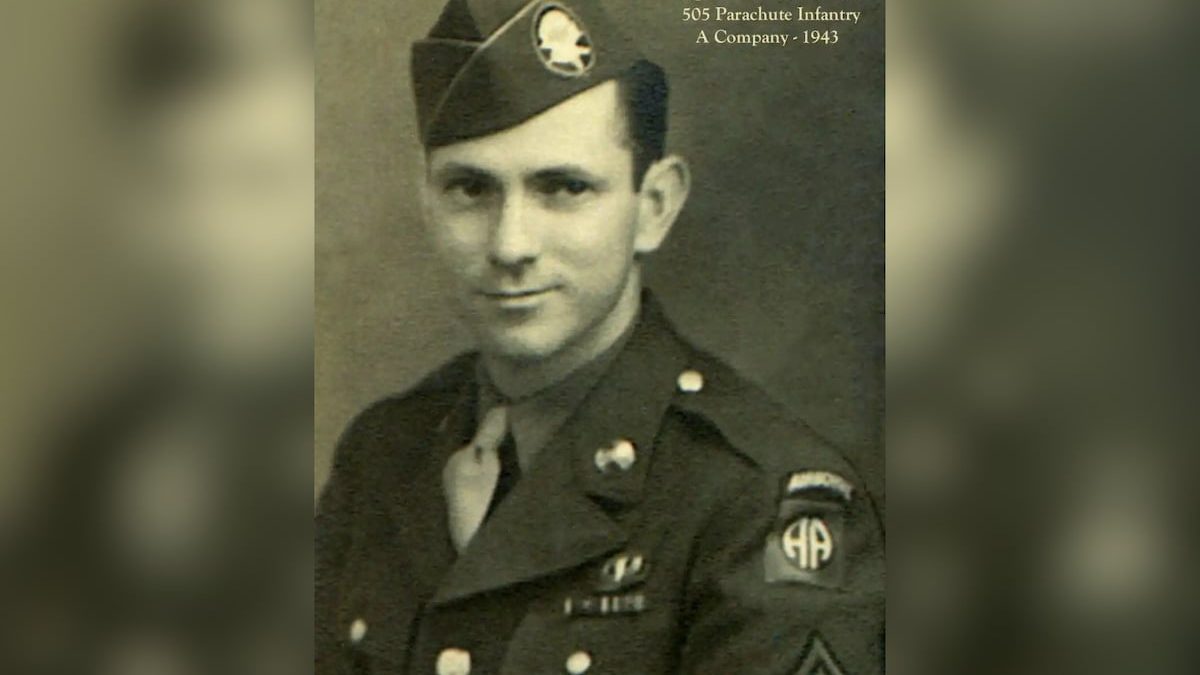

Army Staff Sgt. William D. Owens knew his platoon was in trouble.

Part of A Company, 505th Parachute Infantry Regiment, 82nd Airborne Division, his platoon had jumped into Normandy on June 6, 1944, and captured La Fiere Bridge, just west of Utah Beach. A day later, after vicious counterattacks by German troops and tanks, Owens had only a few men left to hold the vital crossing across the Merderet River.

Bloodied and outnumbered, they fought on. Owens rallied his men, strengthened their defenses and collected ammunition from the dead and wounded, then single-handedly fired two machine guns and a Browning automatic rifle as hundreds of Germans tried to storm their position.

Four Americans earned the Distinguished Service Cross — second only to the Medal of Honor — for their actions at La Fiere that day, though Owens was not one of them. The men of A Company thought that was unfair. So did retired Army Col. Keith Nightingale, a Vietnam veteran who later led the 505th PIR. When he learned of the oversight, he had to do something about it.

“This is a guy who essentially saved the defensive position of the 505,” Nightingale said. “In doing so, he preserved the strategic objective of the bridge. It struck me emotionally.”

He added, “Gen. Gavin [later commander of the 82nd Airborne] said he deserved the Medal of Honor.”

During a ceremony Thursday at La Fiere Memorial Park in France, Harrison Morales accepted the Distinguished Service Cross on behalf of his great-grandfather, Owens, who died in 1967. The long-overdue award is an upgrade of his Bronze Star. Owens also received the Purple Heart with Oak Leaf Cluster and the Silver Star for Operation Market Garden.

The firefight at La Fiere was one of the fiercest and most important of the Normandy campaign. Elements of the 82nd Airborne held the bridge — actually a causeway between fields flooded by the Germans to prevent parachute drops — against several bloody counterattacks. Failure here would have seriously jeopardized the D-Day landings by preventing the U.S. Army’s 4th Infantry Division and 70th Tank Battalion from moving inland from Utah Beach.

Military journalist S.L.A. Marshall, author of “Night Drop: The American Airborne Invasion of Normandy,” claimed La Fiere Bridge was “probably the bloodiest small unit struggle in the experience of American arms.”

With the aid of 44 men in his platoon, Owens captured the bridge in the wee hours of June 6. Over the next 48 hours, they held their ground against three German tanks, which were destroyed by a pair of two-man bazooka teams. Owens scared off a fourth tank by braving enemy fire so he could get close enough to toss Gammon grenades.

“Owens is one of the premier heroes,” said James Donovan, author of the newly published “Nothing But Courage: The 82nd Airborne’s Daring D-Day Mission — and Their Heroic Charge Across the La Fiere Bridge.”

“Not only did he prevent a sneak German attack by crawling along to throw two grenades, but he directs the defense for the next two days,” Donovan said. “He was the key.”

During the battle, the staff sergeant saw his force dwindle from 45 to just 12 effectives. Owens, who became company commander when his lieutenant was mortally wounded, took charge and repositioned his soldiers to stop three German assaults. He crawled between foxholes to gather ammunition from casualties and even propped up dead soldiers to make them appear alive. For one attack, Owens by himself fired two machine guns whose crews had been killed or wounded. When the barrel of one overheated, he blasted away with a Browning automatic rifle until he ran out of ammunition.

Years later, when Marshall interviewed 505th PIR soldiers about what happened, he was told by nearly everyone, “The defense was saved by Owens. It was his courage and calmness which made us stick [it] out. He carried the load.”

“Owens is providing critical leadership at a crucial time and he is directly involved in combat under circumstances that are very, very impressive,” said military historian Martin K.A. Morgan, author of “Down to Earth: The 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment in Normandy.”

“His citation for the Distinguished Service Cross shows him cradling and firing a machine gun. That’s super soldier stuff right there.”

Lt. Gen. James Gavin, commanding officer of the 505th PIR, witnessed Owens in action and nominated him for the Medal of Honor, which was declined. Battalion commander Lt. John J. Dolan backed him for a Distinguished Service Cross but the paperwork was lost.

Nightingale discovered this oversight about five years ago. He worked passionately to rectify the omission and make sure Owens’ family would receive the medal, which was upgraded from a Bronze Star.

“This guy goes from being a squad leader to company commander in the course of a couple of hours,” Nightingale said. “He was lost in history, and I thought that was not a good idea. We had a lost valor.”

Read the full article here