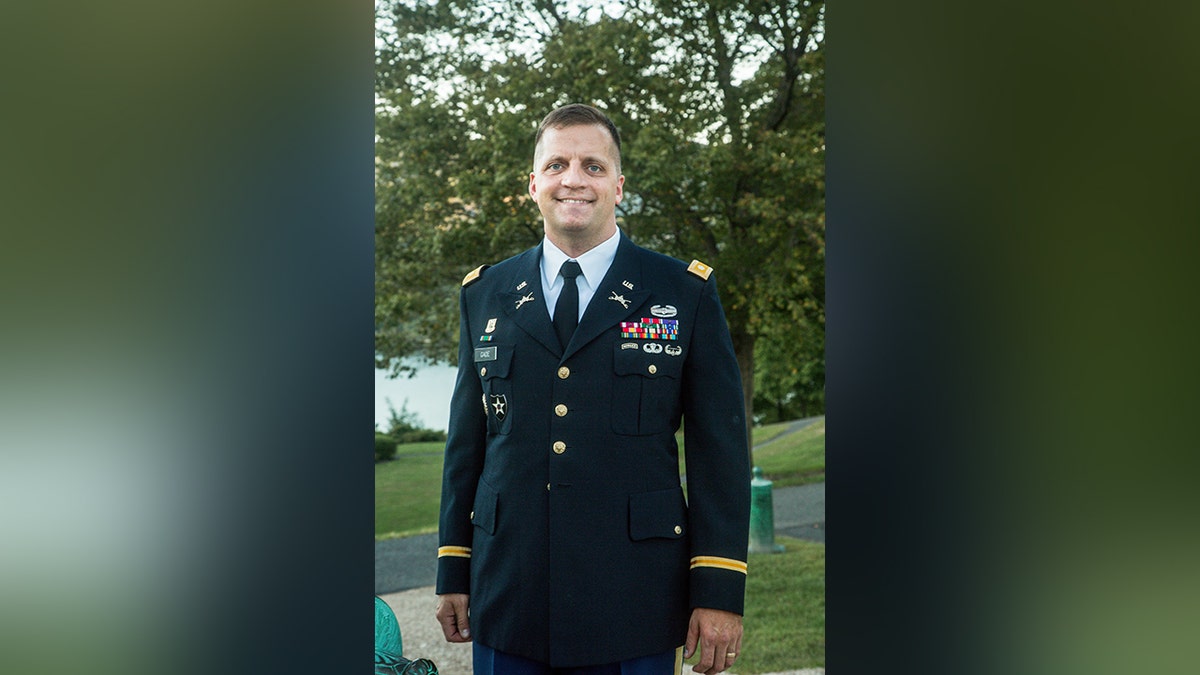

Retired U.S. Army Lt. Col. Daniel Gade, a wounded soldier who refused to let the enemy win and built a career helping other soldiers in the classroom, is now assisting veterans as they cope with returning to normal life while facing dark times and possibly suicide.

The Department of Veterans Affairs’ (VA) National Veteran Suicide Prevention annual report, released in December 2024, revealed there were 47,891 suicides among all U.S. adults in 2022, averaging just over 131 per day. The numbers included 17.6 veteran suicides per day.

Gade, a two-time Purple Heart recipient, serves as a senior advisor for America’s Warrior Partnership (AWP), which has a mission to partner with communities to prevent veteran suicide, while also helping communities figure out how to provide for their veterans.

Through academic research with Duke University and other institutions, along with state and local agencies, AWP found that the veteran suicide rate is much higher than what is reported.

BIPARTISAN BILL WOULD MAKE IT EASIER FOR MILITARY RECRUITS WITH MEDICAL ISSUES TO LAND DEFENSE JOBS

In fact, the research conducted by AWP and its partners shows the veteran suicide rate is actually higher, Gade said, because many deaths go unreported. The organization, he added, is conducting rigorous research that is getting to some of the root causes of veteran dislocation, a term Gade used because dislocation, or disconnectedness, is “kind of a precondition for suicide.”

“What they’re looking at is the disconnectedness in order to better prevent suicide,” he said. “So, it’s not about dumping money into crisis lines, because by the time somebody calls a crisis line, it’s way too late. And for a lot of people, they never call a crisis line; they just go to the gun safe. And that’s not good enough.”

Instead, the process is about building veterans back up and helping them find their place in society, a process Gade said he personally experienced.

Gade joined the Army in 1992 at the age of 17. A year later, he was accepted into the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in New York. He graduated from the academy in 1997, becoming an armored officer in the Army. Seven years later, he was deployed to Iraq, where he was wounded twice.

‘DOWN TO ZERO’: VETERAN SUICIDE CRISIS TARGETED IN VA BILL BY BIPARTISAN HOUSE COALITION

The first time he was wounded was in November 2004, when the tank he was in was struck by a rocket-propelled grenade. Gade said he was wounded mildly, though a young soldier next to him, Dennis Miller from La Salle, Michigan, was killed in the attack. Two months later, Gade was involved in another attack.

“I was hit by a roadside bomb, an IED [improvised explosive device] that caused me to lose my entire right leg. So, I’m a right leg, hip-level amputee,” he said, adding that the wounds forced him to spend a year in the hospital. “During that time… I had to find a way to rebuild myself.”

Rebuilding meant Gade had to rediscover who he was going to be professionally and personally. It also meant pondering the type of athletics he would be able to do and whether he would be able to provide for his family.

“All of those were really critical questions 20 years ago when I was trying to solve that problem, and since then, I’ve had a great career,” he said.

U.S. SOLDIER WOUNDED DURING GAZA PIER MISSION DIES MONTHS AFTER BEING INJURED

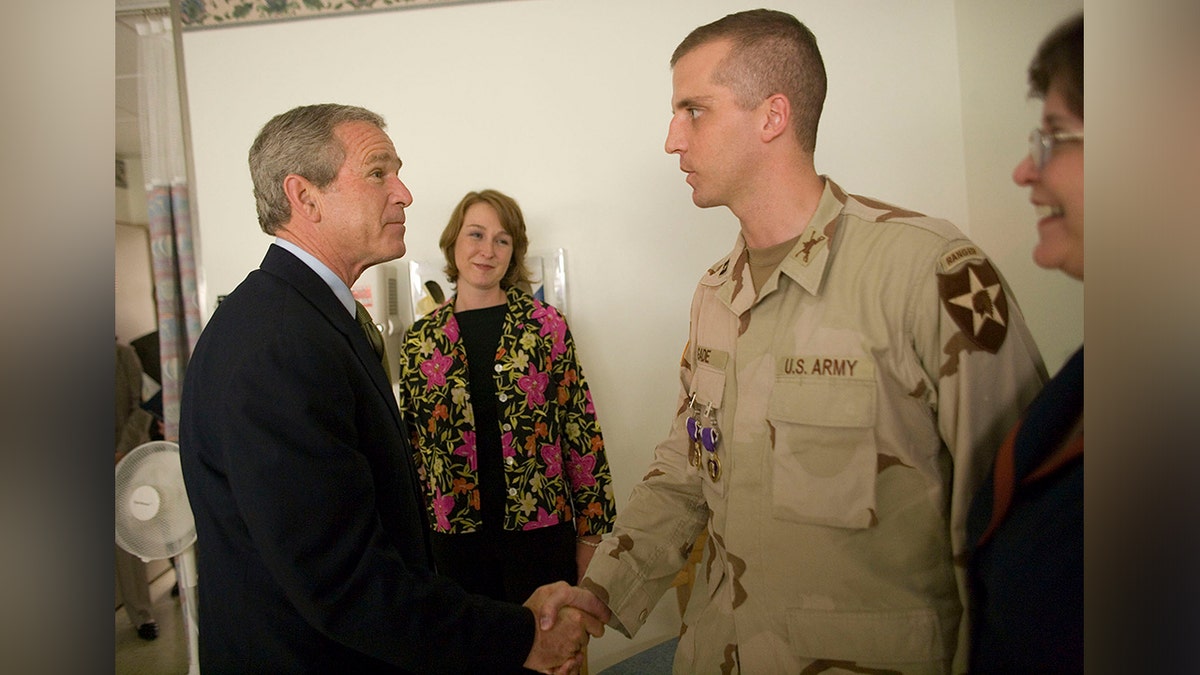

A year to the day after Gade was injured, he started to work on his master’s degree at the University of Georgia. Upon completion, he was invited to the White House to serve as an associate director of the White House Domestic Policy Council under George W. Bush’s administration.

“I went from being sort of a user-level wounded warrior… to being at the very highest levels of government, you know, helping to formulate policy that would help wounded warriors,” Gade said.

Gade retired from the Army in 2017, spending the last six years of his service as a professor at West Point, which he calls “a phenomenal place.”

After that, Gade dabbled in politics, making a run for the U.S. Senate in Virginia in 2020 as a Republican against Democratic Sen. Mark Warner. Gade ultimately lost, but he was able to join Glenn Youngkin’s campaign for Virginia governor as an advisor, and when Youngkin won, Gade was tapped to serve as the commissioner of the Department of Veterans Services.

“I got to go back to my roots, kind of, serving veterans, which is what I’ve done as a personal mission for many years now, basically since I became a wounded warrior back in 2005,” Gade said.

Today, Gade owns a service-disabled, veteran-owned small business called Interfuse, which is involved in chemical and biological defense products for the Air Force, Army and Navy.

BENGHAZI LEGEND MARK GEIST PRESENTS K9 SERVICE DOG TO COMBAT VETERAN IN N.J.

He also continues to help veterans through AWP by connecting veterans to their communities and giving them purpose and value while connecting them with other people. When you do that, Gade said, you find suicidality or the propensity to commit suicide goes down “a good bit.”

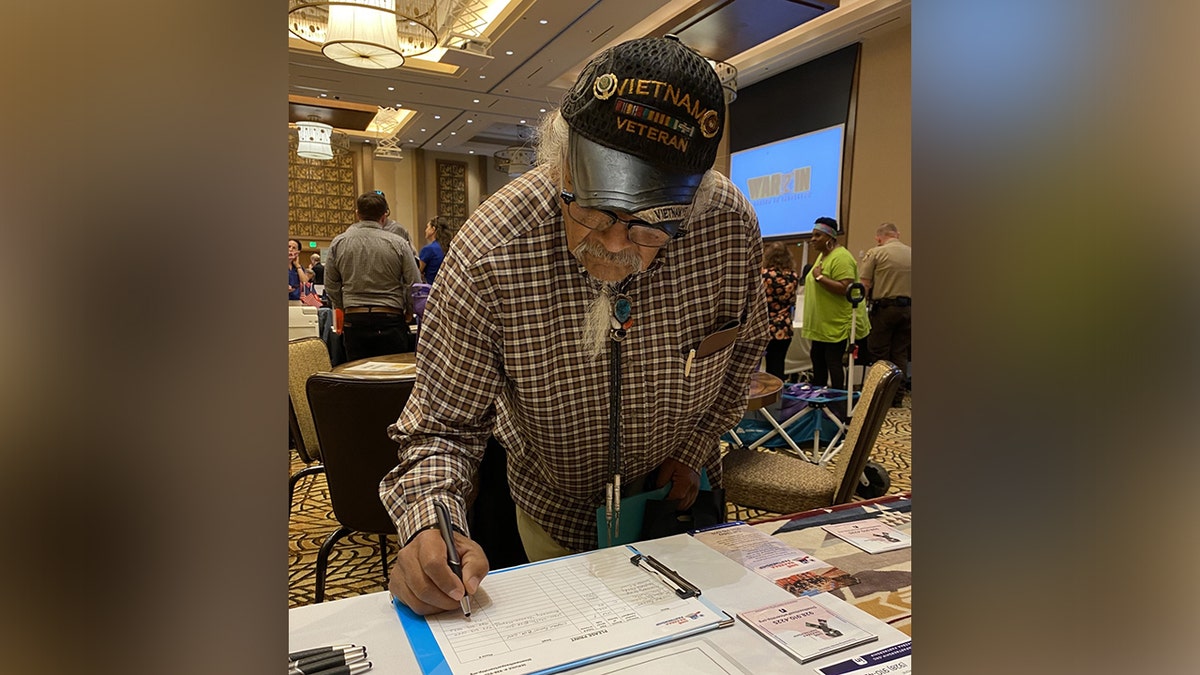

One of the communities the organization has worked with is the Navajo Nation.

“If you think about people in society who are disadvantaged… you always sort of think about, you know, minorities in the inner city or people born into a tough situation like that,” Gade explained. “But very few people know the plight of the American Indian.”

Gade grew up in North Dakota, where the Navajo Nation owns several large reservations. Those reservations, he said, suffer from poverty, alcoholism, dysfunctional families, divorce and many other issues.

He explained that many people in the Navajo Nation join the military because they are patriotic, but also because they are searching for a way to escape and better themselves. Oftentimes, they go on to do great things in the military, Gade said, pointing to the Navajo Code Talkers, who used their native language to create secret codes during World War II.

After serving their country, the tribal members return to their communities, but according to Gade, they bring back post-traumatic stress, physical injuries or other conditions that get laid on top of what were already tough economic and social conditions for them.

“America’s Warrior Partnership, through its connectedness with the Navajo Nation, [is] taking sort of a whole-of-society approach,” Gade said. “It’s not just helping police figure out how you divert somebody instead of arresting somebody. In some cases, you might want to offer them resources so they can escape that path themselves.”

Part of that community connection also gives insight into whom the veterans are, not just to prevent suicide, but also to get better statistics on what is leading to veteran suicide.

AWP created a project called Operation Deep Dive that digs further into veteran causes of death.

FOX NEWS’ PETE HEGSETH OPENS UP ABOUT POST-TRAUMATIC STRESS AFTER IRAQ DEPLOYMENT

While the VA reports a veteran suicide rate of about 17%, AWP found through Operation Deep Dive that the rate is almost double that.

Gade said the difference came down to unreported suicides. For example, there may be a 25-year-old veteran who crashes a vehicle at midnight, but it is not known why he crashed the car. The coroner may just write the cause of death as a single-vehicle accident, but a deeper dive by Operation Deep Dive may look into the person’s life. That same investigation may find the veteran was despairing, had just gone through a divorce or something along those lines.

Another example where Operation Deep Dive may help is if someone has an overdose of a prescription medication prescribed by the VA. The coroner has to determine if it is accidental or suicide, and by doing a deep dive, the organization is finding that the deaths are more likely than not to have been self-harm or accidental self-harm, rather than just pure accidents.

“That’s where the difference comes — it’s expanding our definition of unnatural death to include these others,” Gade said. “And then you realize, oh, man, a whole lot of these are suicides and not just single-vehicle accidents.”

“Every suicide is tragic, but every suicide, you know, suicide is a disease of despair,” he added. “What America’s Warrior Partnership is doing is really trying to get at the roots of that and defeat suicide before it comes into somebody’s life.”

Read the full article here