DON’T CALL IT A 2011

Whether you want to call them double-stack 1911s or 2011s, guns like these used to live solely in the domain of gamers, paraprofessional tinkerers, and shadetree ’smiths. They started gaining popularity in recent years because of the combination of reduced cost, increased reliability, and consumer boredom with plastic pistols.

There are online arguments about what exactly is and is not a 2011, but most of them are merely pedantic quibbling about the Champagne region of France. But let’s cover all the well ackchyually of it.

Despite the name, the origins of the OG 1911 lay in the late 19th century. The most celebrated American firearms inventor, John Moses Browning, first put pen to parchment for this pistol in the 1890s. It was officially adopted as the mass-issue American military pistol on March 29, 1911 — hence the designation. Many variations would be produced for combat use until 1985, when it was usurped by the Beretta M9; some specific spinoffs were still used by select special units through the GWOT era.

While lovers of the 1911 will declare it to be the most respected pistol on the planet, the reality has more to do with proliferation than preference. America pumped out nearly 2 million of them during World War II, and even the Nazis made some in Norway at the same time. After the war, not only did many nations make their own authorized and unauthorized copies and clones, America supplied her allies with surplus and also sold them to the public by the pound. Needless to say, they were cheap and plentiful; the 1911 fit into every gap and crack it could, especially with pistol competitions.

Over the centennial of the 1911 there were a great many variations, but for our purposes discussing the 2011 there are three features to detail:

THREE THINGS YOU NEED FOR A 2011

Doublestack Mags

Every gun with an automatic action relies on a functional magazine to run. The original 1911, shooting the stubby-and-straight .45ACP, has a single-stack, relatively upright magazine. Para Ordnance, a Canadian company founded in the mid 1980s, set out to increase capacity. This northern neighbor produced the first functional double-stack magazines and frames in 1989. These widebodies were fat and heavy, but worked relatively well compared to others, at least in .45ACP and .40S&W.

Beyond the double-stack magazine itself, some stipulate that 2011 magazines must sit upright like the originals. This is said to be to more easily allow the steep 1911 grip angle, but it just as easily serves as an anti-9mm measure, as the caliber doesn’t work well that way.

Today, more as a testament to obdurance than engineering, we have high-capacity, 1911-like magazines in 9mm that actually run.

Modular, Two-Piece Frame

Sandy Strayer and Virgil Tripp, respective founders of Infinity Firearms and Staccato, shared the patent for a two-piece frame and handgrip assembly. This design allowed a pistol to feed from new double-stack mags, but with a more-slim grip. Initially applied for in 1992, the patent was granted on March 15, 1994 — a scratch over six months before the Clinton Crime Bill was signed into law, which restricted the manufacture of magazines over ten rounds.

Reportedly it was Virgil Tripp who first coined the term “2011” (pronounced “twenty-eleven”) back in September 1993. Exactly like how the 1911 is really a 19th century pistol, the 2011 is planted firmly in the 20th — the name sounded very futuristic in a world where Sears catalogs still circulated.

The utility patent for the two-piece frame expired a year after the namesake in 2012, but it would be some years before economies of scale, manufacturing capabilities, and reliability would increase enough for the general public to really take notice.

Made by Staccato

Though the patent for the frame features is now long expired, the trademark is not. A few months before their utility patent was set to expire in July 2012, Staccato successfully trademarked “2011” in regard to firearms.

This is why there are plenty of guns that people and publications will call a 2011, but the manufacturers themselves usually will not. Which brings us to the featured pistol of this piece, Springfield Armory’s 1911 DS Prodigy Comp AOS.

PRODIGY COMP AOS

Springfield Armory released their first Prodigy back in 2022, and we reviewed it in RECOIL Issue 63. While it’s not going to be to everyone’s taste, it brings a bevy of boss features out of the box at a price unheard of for something American-made. (While Springfield imports and rebrands an awful lot of guns, the Prodigy ain’t one of them).

| Brownells | $1,415 |  |

| Palmetto State Armory | $1,350 |  |

| Sportsman’s Warehouse | $1,500 |  |

Available in 4.25-inch (shown) and 5-inch models, it’s ambidextrous, optic-ready with the Agency Optic System, has a great trigger, and is incredibly accurate. The Prodigy shares a grip texture with the Hellcat, something which Springfield Armory dubs Adaptive Grip Texture. And of course, this one is comped.

COMPENSATING

Despite their seemingly interchangeable use in common parlance, ports, brakes, and compensators aren’t the same thing. While they all aim to change the feel of a gun while it runs, the way they go about it are decidedly different.

A muzzle brake is designed to reduce felt recoil, a compensator is for reducing muzzle climb, and both are typically separate devices attached to the end of a barrel. Ports are generally intended to reduce rise but are windows drilled directly into the barrel itself. All of them use ammunition exhaust for operation.

Brakes and comps require gas expansion chambers to be the most effective, pushing gas onto a flat surface before it flows from the device. It’s not the same for ports, though those reduce muzzle velocity and can shave off small pieces of projectile during operation.

So, if ports are cut into barrels, and the Springfield Armory Prodigy Comp has that hole cut into it, isn’t it really a port? Yes. No. Maybe a bit of both.

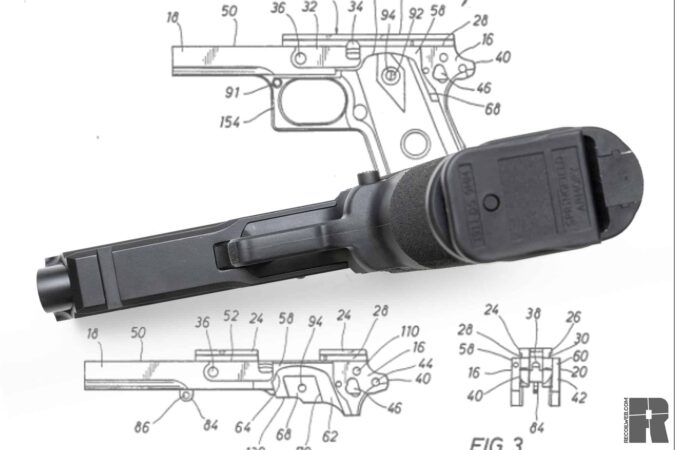

Though there’s a large hole cut directly into the barrel, the Prodigy Comp has what’s essentially an integral compensator rather than a traditional ported setup. The heavy match-grade bull barrel allowed Springfield to machine an expansion chamber into the end of the barrel itself rather than attaching it after.

Does it work? Absolutely. There have been a number of aesthetic brakes and other devices out there, many of which require the use of hot ammunition to actually do anything, but this gun runs flat as hell with everything. Though it should be stated that a steel pistol that weighs a hair over 3 pounds with an optic and fully fueled doesn’t exactly bounce around under recoil. Ripping through mags on the range is a helluva good time here.

We’ve yet to encounter any real issues, but when we’re talking 9mm 2011s it just means we haven’t put enough rounds through it. These guns are a little more complex, which means they take a little more time, care, and consideration.

LOOSE ROUNDS

Any handgun with a 1911 action that feeds from a double-stack mag, especially if it’s chambered in 9mm, at minimum it can be casually called a “2011” for shorthand. And if it has a two-piece frame on top of that, it can definitely be called 2011. Like Q-Tips, Kleenex, Vaseline, and Velcro, 2011 is a trademark that’s become part of common language.

The original 1911 was designed in a time when machine labor was very expensive and man labor was cheap. While we live in an opposite time, where hand fitting always comes with a premium, we finally have the machines, designs, and knowhow to really push the envelope of what’s possible without having to shell out for a custom ’smith.

| Brownells | $1,415 |  |

| Palmetto State Armory | $1,350 |  |

| Sportsman’s Warehouse | $1,500 |  |

No 2011 is a beginner blaster, including this one. But it’s also no longer solely relegated to the realm of nerds and wizards who want to swap springs and triggers and otherwise spend their free time tuning. In part this is because of the price, but the larger part is what you’re getting for the price you pay. It wasn’t terribly long ago that this pistol with this level of customization would have cost the same as a decent used car, but no longer.

The 2011 in general and the Prodigy in particular represents the forward, leading edge of our current collective construction capability. The high water mark of mass manufacturing. We have an endless supply of striker-fired plastic 9mm pistols. They’re plentiful, reliable, soulless, and far, far less fun than this one. Give this one a try.

Read the full article here