By Tom Marshall and Dave Merrill

RED DOTS, LPVO, & LONG RANGE SCOPES, OH MY.

American manufacturing is better and more accessible than ever. Our collective knowledge and understanding of the AR-15 platforms has resulted in mid-market rifles in 2021 with more accuracy potential than the premiums of the past.

The modern AR-15 is the most accurate and reliable mass-produced rifle in all of human history. In fact, there’s a strong argument to be made that ARs are now mechanically outclassing the optics being made for them. That’s not to say the optics industry is lagging or resting on its laurels — that’s simply not true.

What’s happening is that the mechanical accuracy of ARs is evolving in a specific way that’ll necessitate a new class of scope optimized for them.

And it’s not that ARs are getting more accurate — it’s that those more accurate rifles are getting shorter. During recent testing of a prototype 5.56mm barrel, we made an 880-yard hit on steel with a 12.5-inch barrel, while running a 1-10x Low-Powered Variable Optic (LPVO).

Similarly, while testing an 11.5-inch AR chambered in 6mm ARC, we hit at 1,000 yards and only stopped there because the range didn’t go any farther. In that instance, we also used a 1-10x.

What we realized in both cases is that, in the 800-yard-plus arena, it wasn’t the barrel or the ammo holding us back — it was having just-barely-enough magnification to get a good clean look at the target.

In parallel, we’d argue that optics development in recent years has focused on two primary efforts:

- Making high magnification optics smaller (such as EOTech’s 5-25x VUDU)

- Making already-smaller LPVOs higher-powered

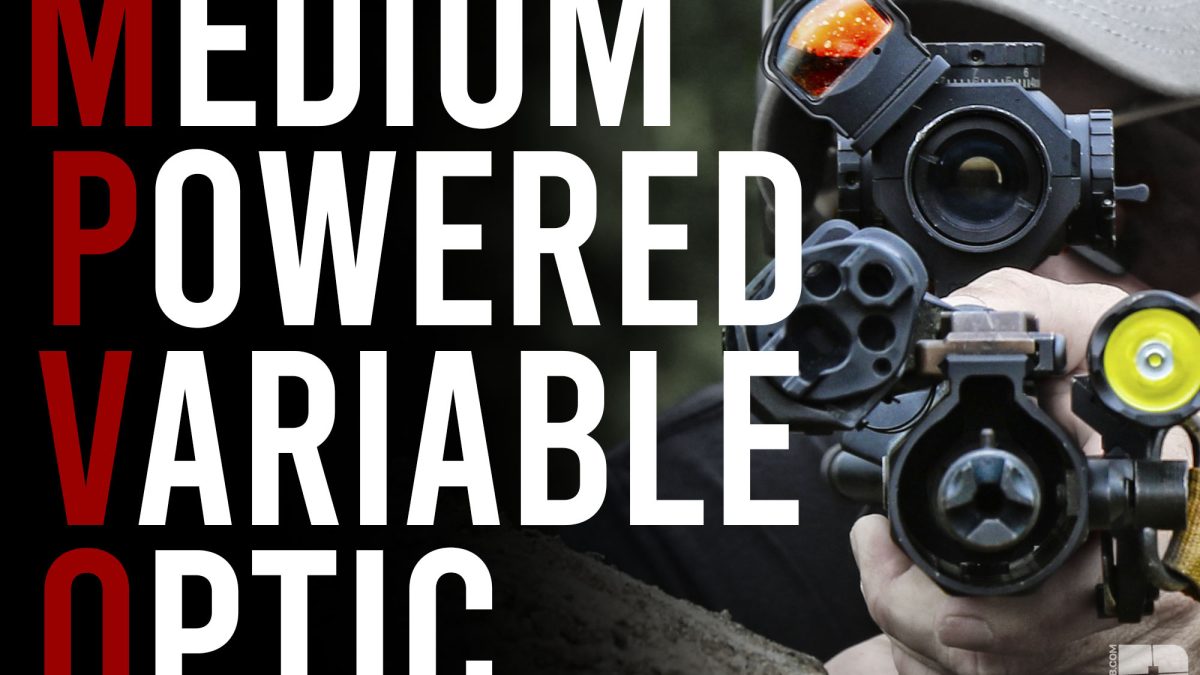

So what to do when 5-25x is too much glass but 1-10x isn’t quite enough? This is our pitch — if not our plea — to the optics market: The next generation of optics should be the Medium-Powered Variable Optic (MPVO).

Essentially, we define an MPVO as a midrange variable stuffed into an LPVO shell, while addressing the downsides of each. There’s more nuance and consideration that we’ll delve into, but that’s the broad strokes.

MPVO APPLICATIONS

The MPVO wouldn’t be the one-optic-to-rule-them-all. This category would be tailored specifically to shorter rifles capable of longer ranges.

Bridging the gap between big tubes on big rifles and low power on little rifles, the MPVO is for any situation where you’d otherwise want to use a traditional scope, except that the rifle needs to stay handy and retain an immediate close-quarters capability through the use of secondary optic, an MRDS.

If you’re already humping a 20-inch-plus barreled rifle, you can stay with what you have. But if you have a smaller recce rifle like our short SCAR Mk20 or an SBR with much greater precision potential like the aforementioned short-barreled Lantac 6ARC, you’ll want an MPVO.

These are guns whose users may find themselves shooting at any distance from 1 to 1,000 yards, depending on the situation.

Their rifle is short enough to clear rooms but accurate enough to place accurate fire at a kilometer. Whether your rifle is a professional tool, self-defense tool, game-getter, match-winner, or any combination thereof, if you’re currently using an LPVO and red dot combination, you could probably be better served by the MPVO concept.

It’ll retain the dirty close speed of an MRDS while amplifying your long-range capability by providing magnification more appropriate to the maximum effective range of your weapon.

WHISKEY 5

As Dan Brokos discussed in depth in his “Evolution of the Combat Optic” article, there have been several transitional stages. The ideal general-purpose optic should maximize the capabilities of your rifle from mere feet away to beyond the effective range, and there have been many approaches to achieve this.

It may seem strange given how ubiquitous optics are now, but it wasn’t until very recent history that optics were accepted on defensive rifles by the public at large. Traditionally, optics were mounted on special-purpose weapons like hunting rifles in the civilian world and sniper rifles in the military realm.

Red dot sights (RDS) were the first to amass widespread public use during the aughts, with many Luddites complaining about it (they can still be found bemoaning dots on pistols).

The Marine Corps was the first branch of service to make the leap of equipping their forces en masse with a magnified optic, in the form of the Trijicon ACOG. Designated marksmen with semiautomatic rifles received variable optics, and Big Army filled in the rest of the optic gaps.

First widely used by competitive shooters, the LPVO is now mounted on seemingly every carbine. It’s not hard to see why.

A 1-6x-plus LPVO brings a tremendous amount of flexibility and capability to the table. You’ll see our staff members with them on all manner of short rifles previously relegated to red dot sights. It’s simply the latest-best solution we have for a general-purpose optic.

The ACOG, now a bit long in the tooth, remains a viable combat optic because it does many things “pretty OK” with minimal additional training time. The fixed 4x power of issued ACOGs provides a higher level of accuracy at medium range, a better-than-zero chance of hitting a target at the effective maximum range, and workable up-close capability using the Bindon Aiming Concept.

A different method is to pair a magnifier with a red dot sight for fast up-close work and magnification for medium-range engagements (see our piece on LPVOs versus magnifiers) — bonus points for a red dot with a BDC reticle. Leupold tried something out of the box with their eccentrically mounted D-EVO system.

And now there’s the LPVO and all its variations. We’ve seen 1-4x, 1-6x, 1-8x, and a limited number of 1-10x models, with even higher numbers on the horizon. They have some warts, however.

For the last several years, we’ve increasingly seen miniature red dot sights paired with LPVOs. Here’s why:

SPEED

“An LPVO on 1x is just as fast as a red dot” is a refrain we often hear repeated by well-meaning internet commentators, but when the rubber meets the road, it falls short. Eye relief and viewing angle are more limited with LPVOs. Sure, with a steep learning curve and a ton of rounds downrange, one can get pretty close to an RDS in perfect conditions; heaven help you if you have to shoot from an unconventional or awkward position.

Chances are you aren’t an extreme outlier like Daniel Horner, but you shouldn’t need to be to put fast and effective rounds into target.

We heard the same thing phrased concerning speed about the Bindon Aiming Concept and the Trijicon ACOG way back in OIF II. And what did we do with the ACOG? We piggybacked an MRDS on it. First, it was Doctor Optic sights on top.

Later on, protective wings were added. Finally, Aimpoint Micros were put in offset mounts in front of ACOGs for that speed, at the price of additional cost and weight. Eventually, Trijicon filled its own gap by mounting RMRs atop the ACOG, which helped reduce weight and bulk while providing increased durability.

The LPVO, just like the ACOG, is more often seen now with a secondary MRDS aiming system for many of the exact same reasons. It’s easier, faster, and more flexible.

PASSIVE USE AND PARALLAX

We used to make fun of the Soviet Union for having extremely high optics on their rifles. The USSR required such high optics on rifles with low-bore capabilities like AK-74s for equipment reasons.

Namely, it’s difficult and sometimes impossible to use low-slung optics in conjunction with riot shields and gas masks. These days, skyscraper optic mounts are used by Americans for use with night vision and gas masks. The Russians weren’t stupid; we just didn’t have the proper context of use before we started pointing fingers.

Of course, there are trade-offs. Not only can looking through a tube with a tube turn into an exercise in frustration, unless you have a consistent cheek weld (which many high mounts preclude) you can induce enough parallax error to make the difference between a hit and a miss. (In recent testing, we found a 45-percent reduction in accuracy when viewing the reticle from the edge rather than perfectly aligned, while on maximum power.)

Yet again, the answer to this issue is the addition of an MRDS. It’s easier, faster, and more flexible.

FEATURES OF THE MPVO

As Alex Hartmann wrote in the article, “Everything Wrong With LPVOs,” in RECOIL Issue 51, “As awesome as LPVOs are at the low end, red dot optics are almost always faster — so why not just use both.” We agree wholeheartedly and take this a step further — don’t bother with a 1x low end on an LPVO at all.

Yes, there are already optics like this; we call them regular scopes. What makes an MPVO is more than just the magnification factor; it’s the form factor.

Imagine fitting 2-12x, or even 3-15x, magnification into a tube the size of a current 1-6x LPVO. Yes, we understand some manufacturing compromises will have to be made, in the same way priorities are different for an LPVO versus a precision optic.

Therefore, an MPVO is:

- A variable midrange magnified optic

- The same size as LPVOs

- First focal plane (FFP)

- Designed with dots in mind

VARIABLE MID-RANGE MAGNIFICATION

An MPVO should have a top end of at least 10x (preferably 12x to 15x) with a low-end magnification level of between 2x to 4x.

Even though you don’t need a lot of magnification to make good hits (Marine Corps sniper rifles famously used a fixed 10x scope for decades), optics can be for more than just shooting.

Higher magnifications allow you to make closer observations, better conduct reconnaissance, and more assured positive identification, and it sure doesn’t hurt on smaller limited probability targets if the rifle and shooter are capable.

With a low end between 2x to 4x, in a pinch you’ll still be able to use the Bindon Aiming Concept if your offset red dot were to malfunction or get damaged.

NO LARGER OR HEAVIER

Size and weight are relative parameters, and, between the two, length is more important here. Current LPVO offerings are relatively compact compared to their higher-powered brethren. On the larger end of the scale (in terms of dimensions and magnification), both the Vortex 1-10x and the Atibal X are just over 10 inches long and right above 21 ounces naked.

Compare this to the Steiner T5Xi seen here, which is 29 ounces and change naked. Also, equivalent 3-12x FFP variables can be significantly longer.

The T5Xi is 13 inches compared to the Razor’s 10, taking up valuable real estate on short rifles, getting in the way of slings and controls, and making maneuvering in tight quarters harder.

To cite a specific example, Tom’s personal mini-recce rifle seen here features an 11.7-inch handguard mated to a 12.5-inch barrel.

From the charging handle to barrel threads, we measured a total of 17.25 inches of usable mounting space on the top of the gun. Giving up 13 inches of that for just the scope is pretty significant, especially when you factor in the need for lights, lasers, switches, and your support hand. This is why the size requirement of a prospective MPVO is so critical.

The trade-off of an MPVO would be smaller objective bells and correspondingly reduced light gathering, but we already do that with LPVOs for the sake of footprint. An MPVO doesn’t necessarily have to follow the straight-tube-in-rings factor of current scopes either. Instead, they could be a one-piece design like the Trijicon VCOG, Elcan, or many of the assorted prismatics.

SFP VS FFP

Second focal plane (SFP), in practical terms, means that the functionality of the reticle (accurate milling or use of BDC marks) is fixed to a certain magnification, typically the highest, regardless of the ability to adjust magnification across a spectrum. The reticle appears the same regardless of the zoom setting.

First (or front) focal plane (FFP) optics have a reticle that scales relative to the magnification. Therefore, the markings will be accurate and usable at any magnification; however, the reticle will appear to grow larger or smaller as you zoom.

SFP optics are typically less expensive to manufacture, lighter in weight, and “daylight bright” illumination is easier to accomplish.

Though choice of SFP versus FFP often comes down to personal preference and style of shooting, when magnifications enter the realm of 8x and up, we have a heavy preference for FFP. You’re more likely to find yourself in situations where you don’t want to max out magnification but still want a properly scaled reticle.

DESIGNED WITH DOTS IN MIND

Whether it’s a short Picatinny rail or direct-mount footprint, on the optic itself or the mount … or even on a separate standalone mount … one of the key features of the MPVO is that it’s designed from the outset with “in-conjunction” in mind.

Those who already have an LPVO with a piggybacked or offset MRDS for use in CQB, unconventional shooting positions, or for night vision, the usefulness of that 1x low end on your LPVO is just about zero.

This is part of the core of our MPVO theory — since 1x functionality is very quickly being supplanted by an in-conjunction red dot, eliminate it altogether to push the high-end magnification higher while still maintaining a form factor friendly to the growing number of distance-capable small rifles.

This is our argument for the next class of optics, the MPVO. We’d really love to be using them.

Read the full article here